A decade ago, marine biologist Mya Breitbart compared genetic sequences of ocean-dwelling viruses against a database by hand, painstakingly analyzing one at a time and entering her results into a spreadsheet.

The field of marine genomics has come a long way since then, with advances in technology and researchers’ newfound computer programming skills making such efforts faster and easier.

“Now I get half a million sequences and don’t even think anything of that,” said Breitbart, a faculty member at the University of South Florida. “It’s changing really, really quickly.”

Breitbart was among the instructors in an intensive course at UD’s Delaware Biotechnology Institute (DBI) recently on bioinformatics, the management and analysis of biological data using math and computer science.

The international class was supported through the National Science Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the European BIOTRIANGLE project and the EU-U.S. Task Force on Biotechnology Research to assist young researchers in handling huge amounts of data in marine genomics.

“A big issue is that now we have so much data coming out of the field, but as biologists, we’re not trained in computation,” said course organizer Jennifer Biddle, assistant professor of marine biosciences in UD’s College of Earth, Ocean, and Environment.

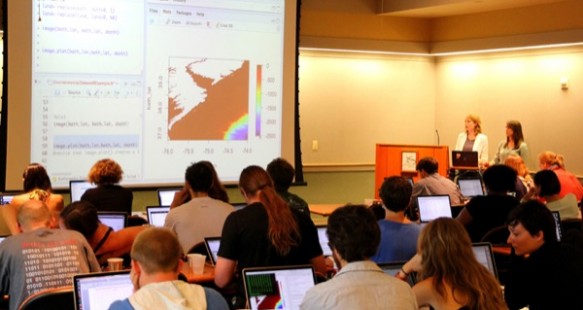

Graduate students and postdoctoral researchers from Europe and the United States spent two weeks in June learning about genetic sequencing technology, trying their hands at sophisticated computer programs and observing how others are tackling data in their work.

“We’re trying to teach marine scientists how to also be computer scientists,” Biddle said.

Biddle, who uses genetic methods to study microbes living under the seafloor, was largely self-taught in developing programs to handle millions of DNA sequences to analyze her samples. When she was approached by the EU-U.S. Task Force to help make life easier for up-and-coming researchers, she pointed out that UD is well-equipped to host such a course: UD already offers bioinformatics training, and DBI houses a sophisticated sequencing facility and additional infrastructure that many institutions lack.

Heather Fullerton, a postdoctoral researcher at Western Washington University who studies microbes at hydrothermal vents, attended the course to fine-tune her skills in genome assembly. Currently she is working with about 80 gigabytes worth of raw sequence data that she had processed at DBI.

“We have such big data,” Fullerton said. “So how do I deal with that? How do I make sense of it? How do I add in all the environmental variables to it? We have a lot of ecology questions that we want to answer, and we can’t really do that without a level of programming.”

Course co-organizer Frank Oliver Glöckner of the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology ran a similar course in Bremen, Germany, last year and helped facilitate the one at UD with Biddle. During the first week, the group covered key concepts and in the second week they learned implementation and tools. All participants work in the field of marine genomics, whether in coastal areas, the deep sea or extreme environments.

The skills they acquired will help them back in the lab, and part of their acceptance into the training course requires sharing techniques with fellow students back at their own universities. They will also have an expanded network of colleagues to help troubleshoot future challenges in their research, which was another goal of the effort.

“So it’s not only to share information and how to process the data, but also to build a network of young researchers,” Glöckner said.

Article by Teresa Messmore

Photos by Kathy F. Atkinson and Frank Oliver Glöckner

Thirty students from Europe and the United States participated in the two-week conference.

Graduate students and postdoctoral researchers learned computer science techniques to analyze large quantities of marine genomics data.