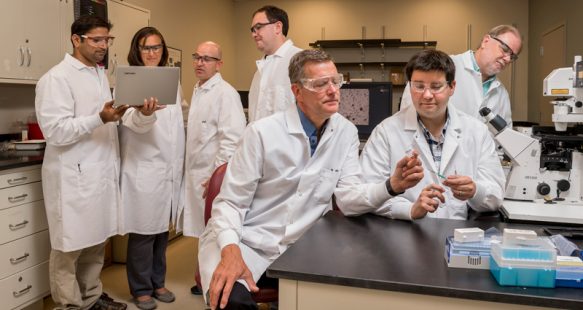

The University of Delaware’s K. Eric Wommack, deputy dean in the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, will lead a research team from four universities that has received a $6 million grant to probe how viruses impact microbes critical to our lives, from producing oxygen to growing food.

Also, UD’s Kelvin Lee, Gore Professor of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, is a co-investigator on a $6.1 million research project, led by Clemson University, aimed at lowering drug manufacturing costs.

The two four-year projects were announced by the National Science Foundation’s Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research (EPSCoR) on Wednesday, Aug. 2. They are among eight projects across the United State, totaling $41.7 million, that aim to build U.S. research capacity in understanding the relationship in organisms between their genes and their physical characteristics. Uncovering this genotype-to-phenotype relationship holds potential for improved crop yields, better prediction of human disease risk and new drug therapies.

“Over the past several decades, scientists and engineers have made massive strides in decoding, amassing and storing genomic data,” said Denise Barnes, NSF EPSCoR head. “But understanding how genomics influence phenotype remains one of the more profound challenges in science. These awards lay the groundwork for closing some of the biggest gaps in biological knowledge and developing interdisciplinary teams needed to address the challenges.”

“The University of Delaware’s deep involvement in two EPSCoR grants underscores the world-class leadership and bold ideas of our faculty, as well as the powerful role of interdisciplinary collaboration for society’s behalf,” said Charlie Riordan, vice president of research, scholarship and innovation. “We congratulate Eric and Kelvin and look forward to the new technologies their teams will advance.”

In water and soil to the human gut, you’ll find single-celled microbes — and viruses right alongside them. A virus will infect a microbe, hijack its machinery and begin replicating, eventually killing the host. But how these processes work within complex microbial communities is still largely a mystery.

The multi-university collaboration that UD’s Wommack is leading will develop new technology to enable scientists to examine — in a droplet of water smaller than mist — how a single virus and a single microbial cell interact.

“Imagine doing a classic microbiology experiment with test tubes and culture plates. Our research would take all of those test tubes and cultures and reduce them down to a tiny droplet 100 times smaller than the diameter of a human hair,” says Wommack, who is an expert in environmental microbiology.

Operating under the principle that oil and water don’t mix, the interdisciplinary team will create devices the size of a microscope slide, equipped with tiny incubation chambers filled with oil, to isolate individual droplets of water injected with a syringe. Molds for these microfluidic devices will be fabricated in UD’s state-of-the-art Nanofabrication Facility for collaborators David Dunigan and Jim Van Etten at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Grieg Steward and Kyle Edwards at the University of Hawaii-Manoa, and Marcia Marston and Koty Sharp at Roger Williams University in Rhode Island.

“A big aim of our project is to democratize the microfluidics technology we develop so that the average lab can run these experiments,” Jason Gleghorn, assistant professor of biomedical engineering at UD, says. “It’s about making new tools and resources available to the broader scientific community.”

The research team also will create the Viral Informatics Resource for Genome Organization (VIRGO).

“We have troves of genomic data on viruses,” Wommack says. “What’s limiting our work is that we don’t know the connections between the genes and what the viruses do biologically. How quickly do viruses infect a host? How long do they take to reproduce? What happens to the infected cell? Once we have that information in VIRGO, we can look at a viral community and make inferences about how unknown viral populations will behave.”

A big aim of our project is to democratize the microfluidics technology we develop so that the average lab can run these experiments…. It’s about making new tools and resources available to the broader scientific community.

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR, BIOMEDICAL ENGINEERING

Collaborators in Nebraska, Hawaii and Rhode Island will focus on viruses that infect phytoplankton — microscopic organisms that live in the salty ocean to freshwater lakes and conduct photosynthesis.

Phytoplankton serve as big links in food chains and produce more than half the oxygen on Earth. They, along with other microbes, process as much as 70 percent of the carbon going through ecosystems, according to Wommack.

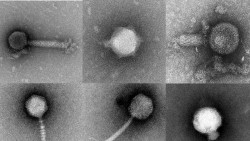

Meanwhile, researchers at UD will focus on viruses that attack microbes important to the nitrogen cycle.

They have a collection of symbiotic bacteria, called Bradyrhizobia, that provide nitrogen to soybean — fueling plant growth without extra fertilizers. Soybean feeds some 2 billion people globally, and more of it will be needed to feed a world population expected to hit 9 billion by 2050.

“We can’t simply fertilize our way to greater agricultural productivity,” Wommack says. “But if we can find a way to improve the plant’s innate nutrition system through research we’re doing now, we may be able to get a plant to do what it already does, a lot better.”

Wommack also has teamed up with Rob Ferrell, science teacher in the Appoquinimink School District, to translate the research into life science and earth science curriculum activities for middle school students.

Other UD members of the project include Barbra Ferrell, research associate; Jeffry Fuhrmann, professor of plant and soil sciences; Jason Gleghorn, assistant professor of biomedical engineering; Shawn Polson, associate professor of computer and information sciences; and Jaysheel Bhavsar, bioinformatics programmer.

The EPSCoR project at Clemson University seeks better ways to engineer Chinese hamster ovary cells, which are used to manufacture more than half of biopharmaceuticals. Joining co-investigator Kelvin Lee on the project will be Cathy Wu, Edward G. Jefferson Chair of Bioinformatics and Computational Biology at UD.

Products from these cells are used in drugs to treat Crohn’s disease, severe anemia, breast cancer and multiple sclerosis, and represent more than $70 billion in sales each year, according to a Clemson news release.

Lee, who directs the National Institute for Innovation in Manufacturing Biopharmaceuticals (NIIMBL), said the EPSCoR project would help address challenges in making these medicines more widely available.

NIIMBL, announced in December 2016 at UD and launched in March 2017, was established with a $70 million grant from the National Institute of Standards and Technology in the U.S. Department of Commerce and with support from more than 150 collaborators.

Article written by: Tracey Bryant

UD’s Kelvin Lee is a co-investigator on a $6.1 million research project, led by Clemson University, aimed at lowering drug manufacturing costs. Joining him on the project is UD's Cathy Wu.

These transmission electron micrographs show viruses of soybean bradyrhizobia, which are beneficial bacteria that provide the soybean plant with the nutrient nitrogen.